by John Simkin

Before the invention of printing in the fifteenth century book indexing had limited use as no two copies were the same nor with the same pagination. Indexes from that time are of several kinds:

- lists of terms or phrases

- concordances to the Bible (from the 7th century)

- subject indexes to canonical law (from the 11th century)

- ‘real concordances’ or classified lists of references to theological concepts

- subject indexes to works on ethics, natural philosophy and logic. In some manuscripts headwords and marginal references served as guides to the text.

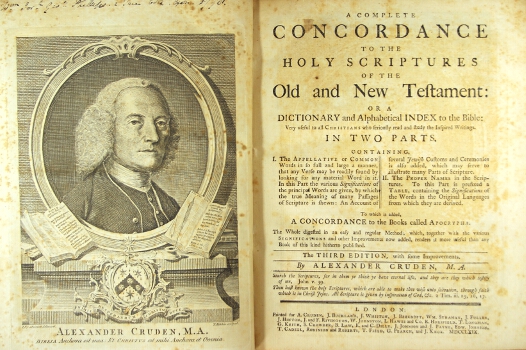

Printed book indexes appeared in the 1460s, almost from the beginning of the era of printing. Developments in medicine were aided by indexes to medical texts and herbals. The first printed Biblical concordance was published in 1544; its compiler was burned for heresy. Of the many subsequent concordances, that by Alexander Cruden — Complete concordance to the Holy Scriptures – first published in 1737, is still in print. Samuel Johnson’s A dictionary of the English language (1755) was a first index to the English language.

In the 19th century there were moves to codify indexing. The Index Society was formed in London in 1877 with the aim of creating ‘a general index of universal literature’. Dr Henry Benjamin Wheatley, after whom the Wheatley Medal is named, wrote What is an indexer? in 1878. This society continued until 1890. Soon afterwards women began to enter the field. Eventually the Society of Indexers was formed in Great Britain in 1957.

In the 19th century there were moves to codify indexing. The Index Society was formed in London in 1877 with the aim of creating ‘a general index of universal literature’. Dr Henry Benjamin Wheatley, after whom the Wheatley Medal is named, wrote What is an indexer? in 1878. This society continued until 1890. Soon afterwards women began to enter the field. Eventually the Society of Indexers was formed in Great Britain in 1957.

Meanwhile in the United States William Frederick Poole began his Index to periodical literature. This was the first of many printed indexes published by the H. W. Wilson Company and others.

During the same period, in Belgium Paul Otlet began the Universal Bibliographic Repertory — a universal index of all knowledge. By 1914 this index contained over eleven million entries backed by text files and illustrations. In this Otlet anticipated the Internet. In 1934 he wrote ‘Traité de documentation: le livre sur le livre, théorie et pratique’ which describes a system by which knowledge would be projected on one’s individual screen so that ‘in his armchair, anyone would be able to contemplate the whole of creation or particular parts of it’.

The Society of Indexers was followed by the founding of indexing societies in the USA (American Society of Indexers, 1968), Australia and New Zealand (Australian Society of Indexers, 1976), Canada (Indexing and Abstracting Society of Canada, 1977), China (China Society of Indexers, 1991) and South Africa (Association of South African Indexers and Bibliographers, 1994). Meanwhile the British Standard on Indexing (BS3700:1976) was published; with its subsequent revisions it is still used throughout the English-speaking world.

From its beginning the computer has been an aid in producing existing forms of indexes and made possible the establishment of large databases. Unfortunately the World Wide Web, the largest accumulation of databases, has developed without any overall plan so that, while some sites use sophisticated indexing techniques, most are only accessible using primitive keyword searches which frequently result in unmanageable numbers of ‘hits’. It is also not subject to any kind of quality control with well-documented and spurious information existing side-by-side, along with advertising and other forms of propaganda.

For the future there is no pressing need to develop new techniques of indexing so much as there is a need to apply those which already exist more effectively especially in making the ever-increasing store of information accessible. In this the profession of indexing is vital.